Toolbox of software data structures, design patterns, algorithms and typical problems. Repo includes swift and typescript examples (add other languages if you feel so). Part of Develepor's toolbox series: link.

Bubble sort, sometimes referred to as sinking sort, is a simple sorting algorithm that repeatedly steps through the list, compares adjacent elements and swaps them if they are in the wrong order. The pass through the list is repeated until the list is sorted. The algorithm, which is a comparison sort, is named for the way smaller or larger elements "bubble" to the top of the list. Although the algorithm is simple, it is too slow and impractical for most problems even when compared to insertion sort. Bubble sort can be practical if the input is in mostly sorted order with some out-of-order elements nearly in position.

| Algorithm | Time Complexity | Space Complexity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best | Average | Worst | Worst | |

| Bubble Sort | Θ(n) | Θ(n^2) | Θ(n^2) | Θ(1 ) |

Example:

func bubbleSort(numbers: [Int]) -> [Int] {

var sortedNumbers = numbers

for i in 0..<sortedNumbers.count {

for j in 1..<sortedNumbers.count-i {

if sortedNumbers[j - 1] > sortedNumbers[j] {

sortedNumbers.swapAt(j - 1, j)

}

}

}

return sortedNumbers

}

let numbers = [5, 15, 14, 1, 26, 0, 99]

print(bubbleSort(numbers: numbers))[0, 1, 5, 14, 15, 26, 99]

Example: jsfiddle link

function bubbleSort(numbers: number[]): number[] {

let sortedNumbers = numbers;

for (let i = 0; i < sortedNumbers.length; i++) {

for (let j = 1; j < sortedNumbers.length; j++) {

if (sortedNumbers[j - 1] > sortedNumbers[j]) {

const temp = sortedNumbers[j - 1];

sortedNumbers[j - 1] = sortedNumbers[j];

sortedNumbers[j] = temp;

}

}

}

return sortedNumbers;

}

const numbers = [5, 15, 14, 1, 26, 0, 99];

console.log(bubbleSort(numbers));[ 0, 1, 5, 14, 15, 26, 99 ]

Insertion sort is a simple sorting algorithm that is relatively efficient for small lists and mostly sorted lists, and is often used as part of more sophisticated algorithms. It works by taking elements from the list one by one and inserting them in their correct position into a new sorted list similar to how we put money in out wallet. In arrays, the new list and the remaining elements can share the array's space, but insertion is expensive, requiring shifting all following elements over by one. Shellsort (see below) is a variant of insertion sort that is more efficient for larger lists.

| Algorithm | Time Complexity | Space Complexity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best | Average | Worst | Worst | |

| Insertion Sort | Ω(n) | Θ(n^2) | Θ(n^2) | Θ(1 ) |

Example:

func insertionSort(numbers: [Int]) -> [Int] {

var sortedNumbers = numbers

for i in 0..<sortedNumbers.count {

let val = sortedNumbers[i]

for j in 0..<i {

if sortedNumbers[j] > sortedNumbers[i] {

sortedNumbers.remove(at: i)

sortedNumbers.insert(val, at: j)

}

}

}

return sortedNumbers

}

let numbers = [5, 15, 14, 1, 26, 0, 99]

print(insertionSort(numbers: numbers))[0, 1, 5, 14, 15, 26, 99]

Example: jsfiddle link

function insertionSort(numbers: number[]): number[] {

let sortedNumbers = numbers;

for (let i = 1; i < sortedNumbers.length; i++) {

let value = sortedNumbers[i];

let position = i;

while (position > 0 && sortedNumbers[position - 1] > value) {

numbers[position] = numbers[position - 1];

position -= 1;

}

numbers[position] = value;

}

return sortedNumbers;

}

function insertionSort2(arr: number[]): number[] {

for (let i = 1; i < arr.length; i++) {

for (let sortedJ = 0; sortedJ <= i; sortedJ++) {

if (arr[i] < arr[sortedJ]) {

const t = arr[i];

arr.splice(i, 1);

arr.splice(sortedJ, 0, t);

}

}

}

return arr;

}

const unsortedArray = [5, 15, 14, 1, 26, 0, 99];

console.log(insertionSort(unsortedArray));[ 0, 1, 5, 14, 15, 26, 99 ]

Selection sort is an in-place comparison sort. It has O(n2) complexity, making it inefficient on large lists, and generally performs worse than the similar insertion sort. Selection sort is noted for its simplicity, and also has performance advantages over more complicated algorithms in certain situations.

The algorithm finds the minimum value, swaps it with the value in the first position, and repeats these steps for the remainder of the list. It does no more than n swaps, and thus is useful where swapping is very expensive.

| Algorithm | Time Complexity | Space Complexity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best | Average | Worst | Worst | |

| Selection sort | Ω(n^2) | Θ(n^2) | Θ(n^2) | Θ(1 ) |

Example:

func selectionSort(numbers: [Int]) -> [Int] {

var sortedNumbers = numbers

for i in 0..<sortedNumbers.count-1 {

var minIndex = i

for j in i..<sortedNumbers.count {

if sortedNumbers[j] < sortedNumbers[minIndex] {

minIndex = j

}

}

let temp = sortedNumbers[minIndex]

sortedNumbers[minIndex] = sortedNumbers[i]

sortedNumbers[i] = temp

}

return sortedNumbers

}

let numbers = [5, 15, 14, 1, 26, 0, 99]

print(selectionSort(numbers: numbers))[0, 1, 5, 14, 15, 26, 99]

Example: jsfiddle link

function selectionSort(numbers: number[]): number[] {

let sortedNumbers = numbers;

for (let i = 0; i < sortedNumbers.length - 1; i++) {

let minValueIndex = i;

for (let j = i + 1; j < sortedNumbers.length; j++) {

if (sortedNumbers[j] < sortedNumbers[minValueIndex]) {

minValueIndex = j;

}

}

const temp = sortedNumbers[minValueIndex];

sortedNumbers[minValueIndex] = sortedNumbers[i];

sortedNumbers[i] = temp;

}

return sortedNumbers;

}

const unsortedArray = [5, 15, 14, 1, 26, 0, 99];

console.log(selectionSort(unsortedArray));[ 0, 1, 5, 14, 15, 26, 99 ]

Conceptually, a merge sort works as follows:

- Divide the unsorted list into n sublists, each containing one element (a list of one element is considered sorted).

- Repeatedly merge sublists to produce new sorted sublists until there is only one sublist remaining. This will be the sorted list.

Merge sort takes advantage of the ease of merging already sorted lists into a new sorted list. It starts by comparing every two elements (i.e., 1 with 2, then 3 with 4...) and swapping them if the first should come after the second. It then merges each of the resulting lists of two into lists of four, then merges those lists of four, and so on; until at last two lists are merged into the final sorted list. Of the algorithms described here, this is the first that scales well to very large lists, because its worst-case running time is O(n log n). It is also easily applied to lists, not only arrays, as it only requires sequential access, not random access. However, it has additional O(n) space complexity, and involves a large number of copies in simple implementations.

| Algorithm | Time Complexity | Space Complexity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best | Average | Worst | Worst | |

| Merge Sort | Θ(n log(n)) | Θ(n log(n)) | O(n log(n)) | O(n) |

Example:

func mergeSort(numbers: [Int]) -> [Int] {

// If only one element - already sorted.

if numbers.count == 1 {

return numbers

}

// First, divide the list into equal-sized sublists

// consisting of the first half and second half of the list.

let iMiddle = numbers.count/2

let left = mergeSort(numbers: Array(numbers[0..<iMiddle]))

let right = mergeSort(numbers: Array(numbers[iMiddle..<numbers.count]))

// Recursively sort both sublists.

return compareAndMerge(left: left, right: right)

}

func compareAndMerge(left: [Int], right:[Int]) -> [Int] {

var leftIndex = 0

var rightIndex = 0

var ordered: [Int] = []

while leftIndex < left.count && rightIndex < right.count {

if left[leftIndex] < right[rightIndex] {

ordered.append(left[leftIndex])

leftIndex += 1

} else {

ordered.append(right[rightIndex])

rightIndex += 1

}

}

// Going through leftovers

ordered += Array(left[leftIndex..<left.count])

ordered += Array(right[rightIndex..<right.count])

return ordered

}

var numbers = [5, 15, 14, 1, 26, 0, 99]

print(mergeSort(numbers: numbers))[0, 1, 5, 14, 15, 26, 99]

Example: jsfiddle link

function mergeSort(numbers: number[]): number[] {

// If only one element - already sorted.

if (numbers.length === 1) {

return numbers;

}

// First, divide the list into equal-sized sublists

// consisting of the first half and second half of the list.

const iMiddle = Math.floor(numbers.length / 2);

const leftArray = [];

numbers.forEach((el, index) => {

if (0 <= index && index < iMiddle) {

leftArray.push(el);

}

});

const rightArray = [];

numbers.forEach((el, index) => {

if (iMiddle <= index && index <= numbers.length) {

rightArray.push(el);

}

});

const left = mergeSort(leftArray);

const right = mergeSort(rightArray);

// Recursively sort both sublists.

return compareAndMerge(left, right);

}

function compareAndMerge(left: number[], right: number[]): number[] {

let ordered = [];

let leftIndex = 0;

let rightIndex = 0;

while (leftIndex < left.length && rightIndex < right.length) {

if (left[leftIndex] < right[rightIndex]) {

ordered.push(left[leftIndex]);

leftIndex++;

} else {

ordered.push(right[rightIndex]);

rightIndex++;

}

}

// Going through leftovers

left.forEach((el, index) => {

if (leftIndex <= index && index <= left.length) {

ordered.push(el);

}

});

right.forEach((el, index) => {

if (rightIndex <= index && index <= right.length) {

ordered.push(el);

}

});

return ordered;

}

const unsortedArrayOfNumbers = [5, 15, 14, 1, 26, 0, 99];

console.log(mergeSort(unsortedArrayOfNumbers));[ 0, 1, 5, 14, 15, 26, 99 ]

Quicksort is a divide and conquer algorithm which relies on a partition operation: to partition an array, an element called a pivot is selected. All elements smaller than the pivot are moved before it and all greater elements are moved after it. This can be done efficiently in linear time and in-place. The lesser and greater sublists are then recursively sorted. This yields average time complexity of O(n log n), with low overhead, and thus this is a popular algorithm. Efficient implementations of quicksort (with in-place partitioning) are typically unstable sorts and somewhat complex, but are among the fastest sorting algorithms in practice. The important caveat about quicksort is that its worst-case performance is O(n2); while this is rare, in naive implementations (choosing the first or last element as pivot) this occurs for sorted data, which is a common case. The most complex issue in quicksort is thus choosing a good pivot element, as consistently poor choices of pivots can result in drastically slower O(n2) performance, but good choice of pivots yields O(n log n) performance, which is asymptotically optimal. For example, if at each step the median is chosen as the pivot then the algorithm works in O(n log n). Finding the median, such as by the median of medians selection algorithm is however an O(n) operation on unsorted lists and therefore exacts significant overhead with sorting. In practice choosing a random pivot almost certainly yields O(n log n) performance.

| Algorithm | Time Complexity | Space Complexity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best | Average | Worst | Worst | |

| Quick Sort | Θ(n log(n)) | Θ(n log(n)) | O(n^2) | O(log(n)) |

There few different parititioning schemes, code below uses Lomuto partition scheme; for Hoare's partitioning scheme, Dutch national flag partitioning take a look here.

Example:

func quickSortLomuto(_ numbers: inout [Int], left: Int, right: Int) -> [Int] {

// Recursive, in-place version that uses Lomuto's scheme.

if left < right {

let p = lomutoPartion(&numbers, left: left, right: right)

quickSortLomuto(&numbers, left: left, right: p - 1)

quickSortLomuto(&numbers, left: p + 1, right: right)

}

return numbers

}

func lomutoPartion(_ numbers: inout [Int], left: Int, right: Int) -> Int {

// We use the biggest item as the pivot.

let pivotValue = numbers[right]

// And begin from the smallest left value.

var storeIndex = left

// Partitioning array into four regions:

// [low..i] where values are <= than pivot

// [i+1..j-1] where values are > than pivot

// [j..high-1] values that we haven't looked at yet

// [high] is the pivot.

for i in left..<right {

if numbers[i] < pivotValue {

(numbers[i], numbers[storeIndex]) = (numbers[storeIndex], numbers[i])

storeIndex += 1

}

}

(numbers[storeIndex], numbers[right]) = (numbers[right], numbers[storeIndex])

return storeIndex

}

var numbers = [5, 15, 14, 1, 26, 0, 99]

print(quickSortLomuto(&numbers, left: 0, right: numbers.count-1))[0, 1, 5, 14, 15, 26, 99]

Example: jsfiddle link

function quickSortLomuto(numbers: number[], left: number, right: number): number[] {

// Recursive, in-place version that uses Lomuto's scheme.

if (left < right) {

let p = lomutoParition(numbers, left, right);

quickSortLomuto(numbers, left, p - 1);

quickSortLomuto(numbers, p + 1, right);

}

return numbers;

}

function lomutoParition(numbers: number[], left: number, right: number): number {

// We use the biggest item as the pivot.

const pivotValue = numbers[right];

// And begin from the smallest left value.

let storeIndex = left;

// Partitioning array into four regions:

// [low..i] where values are <= than pivot

// [i+1..j-1] where values are > than pivot

// [j..high-1] values that we haven't looked at yet

// [high] is the pivot.

for (let i = left; i < right; i++) {

if (numbers[i] < pivotValue) {

[numbers[i], numbers[storeIndex]] = [numbers[storeIndex], numbers[i]];

storeIndex++;

}

}

[numbers[storeIndex], numbers[right]] = [numbers[right], numbers[storeIndex]];

return storeIndex;

}

const arrayToSort = [5, 15, 14, 1, 26, 0, 99];

console.log(quickSortLomuto(arrayToSort, 0, arrayToSort.length - 1));[ 0, 1, 5, 14, 15, 26, 99 ]

Selection sort is an in-place comparison sort. It has O(n2) complexity, making it inefficient on large lists, and generally performs worse than the similar insertion sort. Selection sort is noted for its simplicity, and also has performance advantages over more complicated algorithms in certain situations.

The algorithm finds the minimum value, swaps it with the value in the first position, and repeats these steps for the remainder of the list. It does no more than n swaps, and thus is useful where swapping is very expensive.

| Algorithm | Time Complexity | Space Complexity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best | Average | Worst | Worst | |

| Selection sort | Ω(n^2) | Θ(n^2) | Θ(n^2) | Θ(1 ) |

Example:

func selectionSort(numbers: [Int]) -> [Int] {

var sortedNumbers = numbers

for i in 0..<sortedNumbers.count-1 {

var minIndex = i

for j in i..<sortedNumbers.count {

if sortedNumbers[j] < sortedNumbers[minIndex] {

minIndex = j

}

}

let temp = sortedNumbers[minIndex]

sortedNumbers[minIndex] = sortedNumbers[i]

sortedNumbers[i] = temp

}

return sortedNumbers

}

let numbers = [5, 15, 14, 1, 26, 0, 99]

print(selectionSort(numbers: numbers))[0, 1, 5, 14, 15, 26, 99]

Example: jsfiddle link

function selectionSort(numbers: number[]): number[] {

let sortedNumbers = numbers;

for (let i = 0; i < sortedNumbers.length - 1; i++) {

let minValueIndex = i;

for (let j = i + 1; j < sortedNumbers.length; j++) {

if (sortedNumbers[j] < sortedNumbers[minValueIndex]) {

minValueIndex = j;

}

}

const temp = sortedNumbers[minValueIndex];

sortedNumbers[minValueIndex] = sortedNumbers[i];

sortedNumbers[i] = temp;

}

return sortedNumbers;

}

const unsortedArray = [5, 15, 14, 1, 26, 0, 99];

console.log(selectionSort(unsortedArray));[ 0, 1, 5, 14, 15, 26, 99 ]

In computer science, a Linked list is a linear collection of data elements, whose order is not given by their physical placement in memory. Instead, each element points to the next. It is a data structure consisting of a collection of nodes which together represent a sequence. In its most basic form, each node contains: data, and a reference (in other words, a link) to the next node in the sequence. This structure allows for efficient insertion or removal of elements from any position in the sequence during iteration

| Data Structure | Time Complexity | Space Complexity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Worst | Worst | |||||||

| Access | Search | Insertion | Deletion | Access | Search | Insertion | Deletion | ||

| Singly-Linked List | Θ(n) | Θ(n) | Θ(1) | Θ(1) | O(n) | O(n) | O(1) | O(1) | O(n) |

| Doubly-Linked List | Θ(n) | Θ(n) | Θ(1) | Θ(1) | O(n) | O(n) | O(1) | O(1) | O(n) |

Consider the history section of web browsers, where it creates a linked list of web-pages visited, so that when you check history (traversal of a list) or press back button, the previous node's data is fetched.

Another real life example could a be queue/line of persons standing for food in mess, insertion is done at one end and deletion at other. And these operations happen frequent. dynamic queues / stacks are efficiently implemented using linked lists.

Example:

class Node {

var value: Int?

var next: Node?

}

class LinkedList {

var head: Node?

func insert(value: Int) {

print("Inserting: \(value)")

if var iteratingHead = self.head {

while(iteratingHead.next != nil) {

iteratingHead = iteratingHead.next!

}

iteratingHead.next = Node()

iteratingHead.next?.value = value

}

else {

self.head = Node()

self.head?.value = value

}

}

func remove(value: Int) {

print("Removing: \(value)")

if var iteratingHead = self.head {

var lastNode = self.head!

while(iteratingHead.value != value && iteratingHead.next != nil) {

lastNode = iteratingHead

iteratingHead = iteratingHead.next!

}

if iteratingHead.value == value {

if iteratingHead.next != nil {

lastNode.value = nil

lastNode.next = iteratingHead.next

}

else {

lastNode.next = nil

}

}

}

else {

print("It looks like list is not initilezed yet.")

}

}

func printAll() {

print("Printing values:")

if var iteratingHead = head {

while(iteratingHead.next != nil) {

print(iteratingHead.value ?? 0)

iteratingHead = iteratingHead.next!

}

print(iteratingHead.value ?? 0)

} else {

print("List is empty.")

}

print("---")

}

}

var list = LinkedList()

list.printAll()

list.insert(value: 22)

list.insert(value: 33)

list.insert(value: 44)

list.insert(value: 55)

list.insert(value: 66)

list.printAll()

list.remove(value: 33)

list.remove(value: 66)

list.printAll()

list.remove(value: 22)

list.remove(value: 44)

list.remove(value: 55)

list.remove(value: 66)

list.printAll()Printing values:

List is empty.

---

Inserting: 22

Inserting: 33

Inserting: 44

Inserting: 55

Inserting: 66

Printing values:

22

33

44

55

66

---

Removing: 33

Removing: 66

Printing values:

44

55

66

---

Removing: 22

Removing: 44

Removing: 55

Removing: 66

Printing values:

---

Example: jsfiddle link

class LinkedListNode {

public value: number;

public next: LinkedListNode;

}

class LinkedList {

public head: LinkedListNode;

public insert(value: number): void {

console.log(`Inserting: ${value}`);

let iteratingHead = this.head;

if (iteratingHead != null) {

while (iteratingHead.next != null) {

iteratingHead = iteratingHead.next;

}

iteratingHead.next = new LinkedListNode();

iteratingHead.next.value = value;

} else {

this.head = new LinkedListNode();

this.head.value = value;

}

}

public remove(value: number): void {

console.log(`Removing: ${value}`);

let iteratingHead = this.head;

if (iteratingHead != null) {

let lastNode = iteratingHead;

while (iteratingHead.next != null && iteratingHead.next.value === value) {

lastNode = iteratingHead;

iteratingHead = iteratingHead.next;

}

if (iteratingHead.value === value) {

if (iteratingHead.next != null) {

lastNode.value = null;

lastNode.next = iteratingHead.next;

} else {

lastNode.next = null;

}

}

} else {

console.log("It looks like list is not initilezed yet.");

}

}

public printAll(): void {

console.log("Printing values:");

let iteratingHead = this.head;

if (iteratingHead != null) {

while (iteratingHead.next != null) {

if (iteratingHead.value != null) {

console.log(iteratingHead.value);

}

iteratingHead = iteratingHead.next;

}

if (iteratingHead.value != null) {

console.log(iteratingHead.value);

}

} else {

console.log("List is empty.");

}

console.log("---");

}

}

const list = new LinkedList();

list.printAll();

list.insert(22);

list.insert(33);

list.insert(44);

list.insert(55);

list.insert(66);

list.printAll();

list.remove(33);

list.remove(66);

list.printAll();

list.remove(22);

list.remove(44);

list.remove(55);

list.remove(66);

list.printAll();Printing values:

List is empty.

---

Inserting: 22

Inserting: 33

Inserting: 44

Inserting: 55

Inserting: 66

Printing values:

22

33

44

55

66

---

Removing: 33

Removing: 66

Printing values:

44

55

66

---

Removing: 22

Removing: 44

Removing: 55

Removing: 66

Printing values:

---

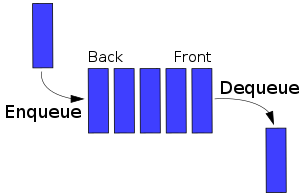

In computer science, a queue is a collection in which the entities in the collection are kept in order and the principal (or only) operations on the collection are the addition of entities to the rear terminal position, known as enqueue, and removal of entities from the front terminal position, known as dequeue. This makes the queue a First-In-First-Out (FIFO) data structure. In a FIFO data structure, the first element added to the queue will be the first one to be removed. This is equivalent to the requirement that once a new element is added, all elements that were added before have to be removed before the new element can be removed. Often a peek or front operation is also entered, returning the value of the front element without dequeuing it. A queue is an example of a linear data structure, or more abstractly a sequential collection.

| Data Structure | Time Complexity | Space Complexity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Worst | Worst | |||||||

| Access | Search | Insertion | Deletion | Access | Search | Insertion | Deletion | ||

| Queue | Θ(n) | Θ(n) | Θ(1) | Θ(1) | O(n) | O(n) | O(1) | O(1) | O(n) |

Ticket counter line where people who come first will get his ticket first.

Key press sequence in keyboard.

Example:

import Foundation

class QNode {

var value: Int?

var next: QNode?

}

class Queue {

var head: QNode?

var tail: QNode?

func enqueue(value: Int) {

print("Enqueing: \(value)")

let node = QNode()

node.value = value

if tail == nil && head == nil {

head = node

tail = node

} else {

tail?.next = node

tail = node

}

// OR

// if tail == nil {

// tail = node

//

// if head == nil {

// head = tail

// }

// }

// else {

// tail?.next = node

// tail = node

// }

}

func dequeue() -> Int? {

print("Dequeing")

if let iteratingHead = head {

head = iteratingHead.next

if iteratingHead.next == nil {

tail = nil

}

return iteratingHead.value

}

else {

print("It looks like queue is not initilezed yet.")

return nil

}

}

func printAll() {

print("Printing values:")

if var iteratingHead = self.head {

while iteratingHead.next != nil {

print(iteratingHead.value ?? 0)

iteratingHead = iteratingHead.next!

}

print(iteratingHead.value ?? 0)

} else {

print("Queue is empty.")

}

print("---")

}

}

let q = Queue()

q.enqueue(value: 11)

q.enqueue(value: 22)

q.enqueue(value: 33)

q.enqueue(value: 44)

q.enqueue(value: 55)

q.printAll()

q.dequeue()

q.dequeue()

q.printAll()

q.dequeue()

q.dequeue()

q.dequeue()

q.dequeue()

q.printAll()Enqueing: 11

Enqueing: 22

Enqueing: 33

Enqueing: 44

Enqueing: 55

Printing values:

11

22

33

44

55

---

Dequeing

Dequeing

Printing values:

33

44

55

---

Dequeing

Dequeing

Dequeing

Dequeing

It looks like queue is not initilezed yet.

Printing values:

Queue is empty.

---

Example: jsfiddle link

class QNode {

public value: number;

public next: QNode;

}

class Queue {

public head: QNode;

public tail: QNode;

public enqueue(value: number): void {

console.log(`Enqueing: ${value}`);

const node = new QNode();

node.value = value;

if (this.tail == null && this.head == null) {

this.head = node;

this.tail = node;

} else {

this.tail.next = node;

this.tail = node;

}

}

public dequeue(): number {

console.log("Dequeing");

let iteratingHead = this.head;

if (iteratingHead != null) {

this.head = iteratingHead.next;

if (iteratingHead.next == null) {

this.tail = null;

}

return iteratingHead.value;

} else {

console.log("It looks like queue is not initilezed yet.");

return 0;

}

}

public printAll(): void {

console.log("Printing values:");

let iteratingHead = this.head;

if (iteratingHead != null) {

while (iteratingHead.next != null) {

if (iteratingHead.value != null) {

console.log(iteratingHead.value);

}

iteratingHead = iteratingHead.next;

}

if (iteratingHead.value != null) {

console.log(iteratingHead.value);

}

} else {

console.log("Queue is empty.");

}

console.log("---");

}

}

let q = new Queue();

q.enqueue(11);

q.enqueue(22);

q.enqueue(33);

q.enqueue(44);

q.enqueue(55);

q.printAll();

q.dequeue();

q.dequeue();

q.printAll();

q.dequeue();

q.dequeue();

q.dequeue();

q.dequeue();

q.printAll();Enqueing: 11

Enqueing: 22

Enqueing: 33

Enqueing: 44

Enqueing: 55

Printing values:

11

22

33

44

55

---

Dequeing

Dequeing

Printing values:

33

44

55

---

Dequeing

Dequeing

Dequeing

Dequeing

It looks like queue is not initilezed yet.

Printing values:

Queue is empty.

---

In computer science, a stack is an abstract data type that serves as a collection of elements, with two principal operations:

- push, which adds an element to the collection, and

- pop, which removes the most recently added element that was not yet removed.

The order in which elements come off a stack gives rise to its alternative name, LIFO (last in, first out). Additionally, a peek operation may give access to the top without modifying the stack. The name "stack" for this type of structure comes from the analogy to a set of physical items stacked on top of each other, which makes it easy to take an item off the top of the stack, while getting to an item deeper in the stack may require taking off multiple other items first.

Considered as a linear data structure, or more abstractly a sequential collection, the push and pop operations occur only at one end of the structure, referred to as the top of the stack. This makes it possible to implement a stack as a singly linked list and a pointer to the top element. A stack may be implemented to have a bounded capacity. If the stack is full and does not contain enough space to accept an entity to be pushed, the stack is then considered to be in an overflow state. The pop operation removes an item from the top of the stack.

| Data Structure | Time Complexity | Space Complexity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Worst | Worst | |||||||

| Access | Search | Insertion | Deletion | Access | Search | Insertion | Deletion | ||

| Stack | Θ(n) | Θ(n) | Θ(1) | Θ(1) | O(n) | O(n) | O(1) | O(1) | O(n) |

Example:

class Stack {

var stackArray = [String]()

func push(val: String) {

self.stackArray.append(val)

}

func pop() -> String? {

if self.stackArray.last != nil {

return self.stackArray.removeLast()

}

else{

return "Stack is empty."

}

}

func printValues() {

print(stackArray)

}

}

let stack = Stack()

stack.push(val: "1")

stack.push(val: "2")

stack.push(val: "2")

stack.push(val: "2")

stack.push(val: "3")

stack.push(val: "2")

stack.push(val: "1")

stack.printValues()

print(stack.pop() as Any)

print(stack.pop() as Any)

stack.printValues()

print(stack.pop() as Any)

print(stack.pop() as Any)

print(stack.pop() as Any)

print(stack.pop() as Any)

print(stack.pop() as Any)

print(stack.pop() as Any)["1", "2", "2", "2", "3", "2", "1"]

Optional("1")

Optional("2")

["1", "2", "2", "2", "3"]

Optional("3")

Optional("2")

Optional("2")

Optional("2")

Optional("1")

Optional("Stack is empty.")

Example: jsfiddle link

class Stack {

private stackArray: string[] = [];

public push(val: string): void {

this.stackArray.push(val);

}

public pop(): string {

if (this.stackArray.length !== 0) {

return this.stackArray.splice(this.stackArray.length - 1, 1)[0];

} else {

return "Stack is empty";

}

}

public printValues(): void {

console.log(this.stackArray);

}

}

let stack = new Stack();

stack.push("1");

stack.push("2");

stack.push("2");

stack.push("2");

stack.push("3");

stack.push("2");

stack.push("1");

stack.printValues();

console.log(stack.pop());

console.log(stack.pop());

stack.printValues();

console.log(stack.pop());

console.log(stack.pop());

console.log(stack.pop());

console.log(stack.pop());

console.log(stack.pop());

console.log(stack.pop());[ '1', '2', '2', '2', '3', '2', '1' ]

1

2

[ '1', '2', '2', '2', '3' ]

3

2

2

2

1

Stack is empty

In computer science, a tree is a widely used abstract data type (ADT) - or data structure implementing this ADT - that simulates a hierarchical tree structure, with a root value and subtrees of children with a parent node, represented as a set of linked nodes. A tree data structure can be defined recursively as a collection of nodes (starting at a root node), where each node is a data structure consisting of a value, together with a list of references to nodes (the "children"), with the constraints that no reference is duplicated, and none points to the root.

Example:

class TreeNode<T> {

public var value: T

public var parent: TreeNode?

public var children = [TreeNode<T>]()

init(value: T) {

self.value = value

}

public func addChild(node: TreeNode<T>) {

children.append(node)

node.parent = self

}

public func printAll() {

print(value)

children.forEach { node in

node.printAll()

}

}

}

let tree = TreeNode(value: "root")

let black = TreeNode(value: "black")

let red = TreeNode(value: "red")

let blue = TreeNode(value: "blue")

let yellow = TreeNode(value: "yellow")

let white = TreeNode(value: "white")

let pink = TreeNode(value: "pink")

tree.addChild(node: black)

tree.addChild(node: blue)

tree.addChild(node: pink)

black.addChild(node: red)

black.addChild(node: yellow)

red.addChild(node: white)

tree.printAll()root

black

red

white

yellow

blue

pink

Example: jsfiddle link

class TreeNode<T> {

public value: T;

public parent: TreeNode<T>;

public children: TreeNode<T>[] = [];

constructor(value: T) {

this.value = value;

}

public addChild(node: TreeNode<T>): void {

this.children.push(node);

node.parent = this;

}

public printAll(): void {

console.log(this.value);

for (let i in this.children) {

this.children[i].printAll();

}

}

}

const tree = new TreeNode("root");

const black = new TreeNode("black");

const red = new TreeNode("red");

const blue = new TreeNode("blue");

const yellow = new TreeNode("yellow");

const white = new TreeNode("white");

const pink = new TreeNode("pink");

tree.addChild(black);

tree.addChild(blue);

tree.addChild(pink);

black.addChild(red);

black.addChild(yellow);

red.addChild(white);

tree.printAll();root

black

red

white

yellow

blue

pink

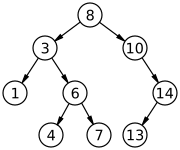

In computer science, a binary search tree (BST), also called an ordered or sorted binary tree, is a rooted binary tree whose internal nodes each store a key greater than all the keys in the node's left subtree and less than those in its right subtree. A binary tree is a type of data structure for storing data such as numbers in an organized way. Binary search trees allow binary search for fast lookup, addition and removal of data items, and can be used to implement dynamic sets and lookup tables. The order of nodes in a BST means that each comparison skips about half of the remaining tree, so the whole lookup takes time proportional to the binary logarithm of the number of items stored in the tree. This is much better than the linear time required to find items by key in an (unsorted) array, but slower than the corresponding operations on hash tables. Several variants of the binary search tree have been studied.

| Data Structure | Time Complexity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Worst | |||||||

| Space | Search | Insertion | Deletion | Space | Search | Insertion | Deletion | |

| Binary Search Tree | Θ(n) | Θ(log n) | Θ(log n) | Θ(log n) | O(n) | O(n) | O(n) | O(n) |

Example: jsfiddle link

class TNode {

public val: number;

public left: TNode;

public right: TNode;

}

class BinarySearchTree {

public root: TNode = null;

public addChild(val: number): void {

const newNode = new TNode();

newNode.val = val;

if (this.root == null) {

this.root = newNode;

} else {

let currentNode = this.root;

let traversing = true;

while (traversing) {

if (currentNode.val < newNode.val) {

if (currentNode.left == null) {

currentNode.left = newNode;

traversing = false;

} else {

currentNode = currentNode.left;

}

} else if (currentNode.val > newNode.val) {

if (currentNode.right == null) {

currentNode.right = newNode;

traversing = false;

} else {

currentNode = currentNode.right;

}

}

}

}

}

public preOrder(): void {

console.log("preOrder");

if (this.root != null) {

let numbers: number[] = [];

let currentNode = this.root;

const traverse = (currentNode: TNode) => {

if (currentNode != null) {

numbers.push(currentNode.val);

traverse(currentNode.left);

traverse(currentNode.right);

}

};

traverse(this.root);

console.log(numbers);

} else {

console.log("Tree is empty");

}

}

public inOrder(): void {

console.log("inOrder");

if (this.root != null) {

let numbers: number[] = [];

let currentNode = this.root;

const traverse = (currentNode: TNode) => {

if (currentNode != null) {

traverse(currentNode.left);

numbers.push(currentNode.val);

traverse(currentNode.right);

}

};

traverse(this.root);

console.log(numbers);

} else {

console.log("Tree is empty");

}

}

public postOrder(): void {

console.log("postOrder");

if (this.root != null) {

let numbers: number[] = [];

let currentNode = this.root;

const traverse = (currentNode: TNode) => {

if (currentNode != null) {

traverse(currentNode.left);

traverse(currentNode.right);

numbers.push(currentNode.val);

}

};

traverse(this.root);

console.log(numbers);

} else {

console.log("Tree is empty");

}

}

public breadthFirstSearchTraversal(): void {

console.log("breadthFirstSearchTraversal");

if (this.root != null) {

let numbers: number[] = [];

let qOfNextItems = [this.root];

while (qOfNextItems.length !== 0) {

const currentNode = qOfNextItems[0];

numbers.push(currentNode.val);

if (currentNode.left != null) {

qOfNextItems.push(currentNode.left);

}

if (currentNode.right != null) {

qOfNextItems.push(currentNode.right);

}

qOfNextItems.splice(0, 1);

}

console.log(numbers);

} else {

console.log("Tree is empty");

}

}

}

const bst = new BinarySearchTree();

bst.addChild(10);

bst.addChild(3);

bst.addChild(0);

bst.addChild(8);

bst.addChild(6);

bst.addChild(15);

bst.addChild(11);

bst.addChild(20);

bst.preOrder();

bst.inOrder();

bst.postOrder();

bst.breadthFirstSearchTraversal();"preOrder"

[10, 15, 20, 11, 3, 8, 6, 0]

"inOrder"

[20, 15, 11, 10, 8, 6, 3, 0]

"postOrder"

[20, 11, 15, 6, 8, 0, 3, 10]

"breadthFirstSearchTraversal"

[10, 15, 3, 20, 11, 8, 0, 6]

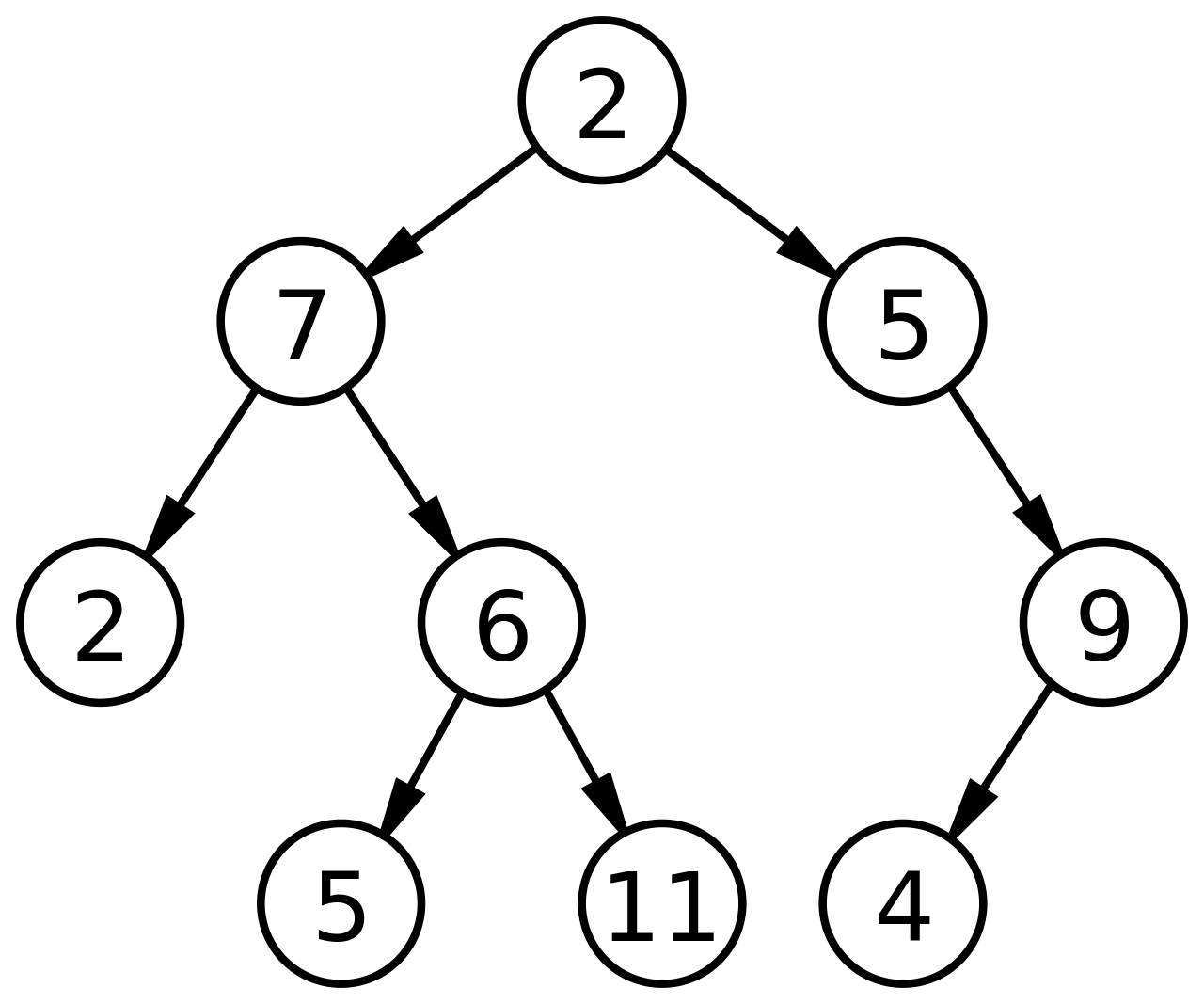

In computer science, a heap is a specialized tree-based data structure which is essentially an almost complete tree that satisfies the heap property: in a max heap, for any given node C, if P is a parent node of C, then the key (the value) of P is greater than or equal to the key of C. In a min heap, the key of P is less than or equal to the key of C. The node at the “top” of the heap (with no parents) is called the root node. The heap is one maximally efficient implementation of an abstract data type called a priority queue, and in fact, priority queues are often referred to as “heaps”, regardless of how they may be implemented. In a heap, the highest (or lowest) priority element is always stored at the root. However, a heap is not a sorted structure; it can be regarded as being partially ordered. A heap is a useful data structure when it is necessary to repeatedly remove the object with the highest (or lowest) priority. A common implementation of a heap is the binary heap, in which the tree is a binary tree. The heap data structure, specifically the binary heap, was introduced by J. W. J. Williams in 1964, as a data structure for the heapsort sorting algorithm. Heaps are also crucial in several efficient graph algorithms such as Dijkstra’s algorithm. When a heap is a complete binary tree, it has a smallest possible height — a heap with N nodes and for each node a branches always has loga N height.

| Data Structure | Time Complexity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | ||||

| Space | Search | Insertion | Deletion | |

| Min Heap (Binary) | Θ(n) | Θ(log n) | Θ(log n) | Θ(log n) |

Example: jsfiddle link

class BinaryMinHeap {

public values: number[] = [];

public insert(val: number): void {

if (this.values.length === 0) {

this.values[0] = val;

} else {

this.values.push(val);

this.bubbleUp();

}

}

private bubbleUp(): void {

let index = this.values.length - 1;

let parentIndex = Math.floor((index - 1) / 2);

let temp;

// Keep looping until the parent node is less than the child node

while (parentIndex >= 0 && this.values[parentIndex] > this.values[index]) {

temp = this.values[index];

this.values[index] = this.values[parentIndex];

this.values[parentIndex] = temp;

index = parentIndex;

parentIndex = Math.floor((index - 1) / 2);

}

}

public extractMin(): number {

if (this.values.length != 0) {

const min = this.values[0];

const end = this.values[this.values.length - 1];

this.values.splice(this.values.length - 1, 1);

if (this.values.length > 0) {

this.values[0] = end;

this.sinkDown();

}

return min;

} else {

return 0;

}

}

private sinkDown(): void {

let parentIdx = 0;

let leftChildIdx = 0;

let rightChildIdx = 0;

let heapLength = this.values.length;

let nodeToSink = this.values[parentIdx];

let idxToSwap = 0;

let swap = false;

// Keep looping through the nodes util you find the right spot

while (true) {

leftChildIdx = 2 * parentIdx + 1;

rightChildIdx = 2 * parentIdx + 2;

swap = false;

let leftChild = null;

let rightChild = null;

// Check with the left child only if it is a valid index

if (leftChildIdx < heapLength) {

leftChild = this.values[leftChildIdx];

// Compare with the node to sink down

if (nodeToSink > leftChild) {

idxToSwap = leftChildIdx;

swap = true;

}

}

// Check with the right child only if it is a valid index

if (rightChildIdx < heapLength) {

rightChild = this.values[rightChildIdx];

if ((swap && leftChild > rightChild) || (!swap && nodeToSink > rightChild)) {

idxToSwap = rightChildIdx;

swap = true;

}

}

if (!swap) {

// If there is no swap required, we found the correct spot for the element

return;

} else {

// Swap the elements

this.values[parentIdx] = this.values[idxToSwap];

this.values[idxToSwap] = nodeToSink;

// Set the reference to index to its new value

parentIdx = idxToSwap;

}

}

}

public printAll(): void {

console.log(this.values);

}

}

const mbh = new BinaryMinHeap();

mbh.insert(2);

mbh.insert(7);

mbh.insert(1);

mbh.insert(0);

mbh.insert(12);

mbh.insert(20);

mbh.insert(25);

mbh.insert(5);

mbh.insert(4);

mbh.printAll();

console.log(mbh.extractMin());

console.log(mbh.extractMin());

console.log(mbh.extractMin());

mbh.printAll();[0, 1, 2, 4, 12, 20, 25, 7, 5]

0

1

2

[4, 5, 7, 25, 12, 20]

It lets you change the behavior of a class when the state changes.

The state pattern is a behavioral software design pattern that allows an object to alter its behavior when its internal state changes. This pattern is close to the concept of finite-state machines. The state pattern can be interpreted as a strategy pattern, which is able to switch a strategy through invocations of methods defined in the pattern's interface.

Imagine you are using some drawing application, you choose the paint brush to draw. Now the brush changes its behavior based on the selected color i.e. if you have chosen red color it will draw in red, if blue then it will be in blue etc.

Authorization system that depending on the state will have user as authorized or unauthorized.

final class Context {

private var state: State = UnauthorizedState()

var isAuthorized: Bool {

get {

return state.isAuthorized(context: self)

}

}

var userId: String? {

get {

return state.userId(context: self)

}

}

func changeStateToAuthorized(userId: String) {

state = AuthorizedState(userId: userId)

}

func changeStateToUnauthorized() {

state = UnauthorizedState()

}

func printAuthorizationStatus() {

print("Is user authorized: \(userContext.isAuthorized). User id is: \(String(describing: userContext.userId)).")

}

}

protocol State {

func isAuthorized(context: Context) -> Bool

func userId(context: Context) -> String?

}

class UnauthorizedState: State {

func isAuthorized(context: Context) -> Bool {

return false

}

func userId(context: Context) -> String? {

return nil

}

}

class AuthorizedState: State {

let userId: String

init(userId: String) {

self.userId = userId

}

func isAuthorized(context: Context) -> Bool {

return true

}

func userId(context: Context) -> String? {

return userId

}

}

let userContext = Context()

// initial state

userContext.printAuthorizationStatus()

// authorizing as admin

userContext.changeStateToAuthorized(userId: "admin")

// now logged in as "admin"

userContext.printAuthorizationStatus()

// unauthorizing

userContext.changeStateToUnauthorized()

// now logged out

userContext.printAuthorizationStatus()Is user authorized: false. User id is: nil.

Is user authorized: true. User id is: Optional("admin").

Is user authorized: false. User id is: nil.

class Context {

private state: State = new UnauthorizedState();

private _isAuthorized: boolean;

get isAuthorized(): boolean {

return this.state.isAuthorized(this);

}

private _userId: string;

get userId(): string {

return this.state.getUserId(this);

}

public changeStateToAuthorized(userId: string) {

this.state = new AuthorizedState(userId);

}

public changeStateToUnauthorized() {

this.state = new UnauthorizedState();

}

public printAuthorizationStatus() {

console.log(`Is user authorized: ${this.isAuthorized}. User id is: ${this.userId}.`);

}

}

interface State {

isAuthorized(context: Context): boolean;

getUserId(context: Context): string;

}

class UnauthorizedState implements State {

public isAuthorized(context: Context): boolean {

return false;

}

public getUserId(context: Context): string {

return `nil`;

}

}

class AuthorizedState implements State {

private userId: string;

constructor(userId: string) {

this.userId = userId;

}

public isAuthorized(context: Context): boolean {

return true;

}

public getUserId(context: Context): string {

return this.userId;

}

}

let userContext = new Context();

// initial state

userContext.printAuthorizationStatus();

// authorizing as admin

userContext.changeStateToAuthorized("admin");

// now logged in as "admin"

userContext.printAuthorizationStatus();

// unauthorizing

userContext.changeStateToUnauthorized();

// now logged out

userContext.printAuthorizationStatus();Is user authorized: false. User id is: nil.

Is user authorized: true. User id is: admin.

Is user authorized: false. User id is: nil.

Define the basic steps of an algorithm and allow the implementation of the individual steps to be changed.

The template method is a method in a superclass, usually an abstract superclass, and defines the skeleton of an operation in terms of a number of high-level steps. These steps are themselves implemented by additional helper methods in the same class as the template method. The helper methods may be either abstract methods, for which case subclasses are required to provide concrete implementations, or hook methods, which have empty bodies in the superclass. Subclasses can (but are not required to) customize the operation by overriding the hook methods. The intent of the template method is to define the overall structure of the operation, while allowing subclasses to refine, or redefine, certain steps.

Suppose we are getting some house built. The steps for building might look like: Prepare the base of house -> Build the walls -> Add roof -> Add other floors.

A flag drawing application: where skeleton class knows how abstractly to draw a 3 color flags, and subclasses know detailed line drawing implementation.

// Define a template method that contains a skeleton of some algorithm, composed of calls to (usually) primitive operations.

protocol TreeColorFlag {

// The template method defines the skeleton of an algorithm.

func draw()

// These operations have to be implemented in subclasses.

func drawFirstPart()

func drawSecondPart()

func drawThirdPart()

}

extension TreeColorFlag {

func draw() {

log(message: "Starting drawing")

drawFirstPart();

log(message: "First part is done.")

drawSecondPart();

log(message: "Second part is done.")

drawThirdPart();

log(message: "Third part is done.")

}

func log(message: String) {

print(message)

}

func drawFirstPart() {

fatalError("Subclass must implement drawFirstPart")

}

func drawSecondPart() {

fatalError("Subclass must implement drawSecondPart")

}

func drawThirdPart() {

fatalError("Subclass must implement drawThirdPart")

}

}

// Concrete classes have to implement all needed operations of the base

// class. They can also override some operations with a default implementation.

class FrenchFlag: TreeColorFlag {

func drawFirstPart() {

print("FrenchFlag says: Implemented Operation1")

}

func drawSecondPart() {

print("FrenchFlag says: Implemented drawSecondPart")

}

func drawThirdPart() {

print("FrenchFlag says: Implemented drawThirdPart")

}

}

class GermanFlag: TreeColorFlag {

func drawFirstPart() {

print("FrenchFlag says: Implemented Operation1")

}

func drawSecondPart() {

print("FrenchFlag says: Implemented drawSecondPart")

}

func drawThirdPart() {

print("FrenchFlag says: Implemented drawThirdPart")

}

}

print("Drawing French 🇫🇷 flag")

FrenchFlag().draw()

print("Drawing German 🇩🇪 flag")

GermanFlag().draw()Drawing French 🇫🇷 flag

Starting drawing

FrenchFlag says: Implemented Operation1

First part is done.

FrenchFlag says: Implemented drawSecondPart

Second part is done.

FrenchFlag says: Implemented drawThirdPart

Third part is done.

Drawing German 🇩🇪 flag

Starting drawing

FrenchFlag says: Implemented Operation1

First part is done.

FrenchFlag says: Implemented drawSecondPart

Second part is done.

FrenchFlag says: Implemented drawThirdPart

Third part is done.

// Define a template method that contains a skeleton of some algorithm, composed of calls to (usually) primitive operations.

class TreeColorFlag {

// The template method defines the skeleton of an algorithm.

draw(): void {

this.log("Starting drawing");

this.drawFirstPart();

this.log("First part is done.");

this.drawSecondPart();

this.log("Second part is done.");

this.drawThirdPart();

this.log("Third part is done.");

}

log(message: String): void {

console.log(message);

}

// These operations have to be implemented in subclasses.

drawFirstPart(): void {

throw new Error("Subclass must implement drawFirstPart");

}

drawSecondPart(): void {

throw new Error("Subclass must implement drawSecondPart");

}

drawThirdPart(): void {

throw new Error("Subclass must implement drawThirdPart");

}

}

// Concrete classes have to implement all needed operations of the base

// class. They can also override some operations with a default implementation.

class FrenchFlag extends TreeColorFlag {

drawFirstPart(): void {

console.log("FrenchFlag says: Implemented Operation1");

}

drawSecondPart(): void {

console.log("FrenchFlag says: Implemented drawSecondPart");

}

drawThirdPart(): void {

console.log("FrenchFlag says: Implemented drawThirdPart");

}

}

class GermanFlag extends TreeColorFlag {

drawFirstPart(): void {

console.log("FrenchFlag says: Implemented Operation1");

}

drawSecondPart(): void {

console.log("FrenchFlag says: Implemented drawSecondPart");

}

drawThirdPart(): void {

console.log("FrenchFlag says: Implemented drawThirdPart");

}

}

console.log("Drawing French 🇫🇷 flag");

new FrenchFlag().draw();

console.log("Drawing German 🇩🇪 flag");

new GermanFlag().draw();Drawing French 🇫🇷 flag

Starting drawing

FrenchFlag says: Implemented Operation1

First part is done.

FrenchFlag says: Implemented drawSecondPart

Second part is done.

FrenchFlag says: Implemented drawThirdPart

Third part is done.

Drawing German 🇩🇪 flag

Starting drawing

FrenchFlag says: Implemented Operation1

First part is done.

FrenchFlag says: Implemented drawSecondPart

Second part is done.

FrenchFlag says: Implemented drawThirdPart

Third part is done.

Adapter pattern lets you wrap an otherwise incompatible object in an adapter to make it compatible with another class.

In software engineering, the adapter pattern is a software design pattern that allows the interface of an existing class to be used as another interface. It is often used to make existing classes work with others without modifying their source code.

Consider that you have some pictures in your memory card and you need to transfer them to your computer. In order to transfer them you need some kind of adapter that is compatible with your computer ports so that you can attach memory card to your computer. In this case card reader is an adapter.

Yet another example would be a translator translating words spoken by one person to another

Power adapter: a two pronged legged US plug can't be connected to an EU outlet, it needs to use a power adapter.

// Adaptee: SocketDenmark contains some useful behavior, but it is incompatible

// with the existing LaptopUS. The SocketDenmark needs some adaptation before the

// LaptopUS can use it.

// 🇩🇰 socket

class SocketDenmark {

public func forbinde() { //connect in Danish

print("Adapee: Forbundet.") // connected in Danish

}

}

// Target: SocketUS defines the domain-specific implementation.

class SocketUS {

func connect() {

print("Target: Connected.")

}

}

/// Adapter: makes SocketDenmark compatible with the SocketUS.

// 🇺🇸 plug to 🇩🇰 socket adapter.

class Adapter: SocketUS {

private var SocketDenmark: SocketDenmark

init(_ SocketDenmark: SocketDenmark) {

self.SocketDenmark = SocketDenmark

}

override func connect() {

print("Adapter: Connecting...")

SocketDenmark.forbinde()

print("Adapter: Connected.")

}

}

// Client: uses Adapter.

// Laptop with 🇺🇸 plug

class LaptopUS {

static func connectUSPlugToElectricity(socket: SocketUS) {

print(socket.connect())

}

}

LaptopUS.connectUSPlugToElectricity(socket: SocketUS())

LaptopUS.connectUSPlugToElectricity(socket: Adapter(SocketDenmark()))Target: Connected.

Adapter: Connecting...

Adapee: Forbundet.

Adapter: Connected.

// Adaptee: SocketDenmark contains some useful behavior, but it is incompatible

// with the existing LaptopUS. The SocketDenmark needs some adaptation before the

// LaptopUS can use it.

// 🇩🇰 socket

class SocketDenmark {

public forbinde(): void {

//connect in Danish

console.log("Adapee: Forbundet."); // connected in Danish

}

}

// Target: SocketUS defines the domain-specific implementation.

class SocketUS {

public connect(): void {

console.log("Target: Connected.");

}

}

/// Adapter: makes SocketDenmark compatible with the SocketUS.

// 🇺🇸 plug to 🇩🇰 socket adapter.

class Adapter extends SocketUS {

private adaptee: SocketDenmark;

constructor(adaptee: SocketDenmark) {

super();

this.adaptee = adaptee;

}

public connect(): void {

console.log("Adapter: Connecting...");

this.adaptee.forbinde();

console.log("Adapter: Connected.");

}

}

// Client: uses Adapter.

// Laptop with 🇺🇸 plug

class LaptopUS {

static connectUSPlugToElectricity(socket: SocketUS): void {

console.log(socket.connect());

}

}

LaptopUS.connectUSPlugToElectricity(new SocketUS());

LaptopUS.connectUSPlugToElectricity(new Adapter(new SocketDenmark()));Target: Connected.

Adapter: Connecting...

Adapee: Forbundet.

Adapter: Connected.

Delegation is a design pattern that enables a class to hand off (or “delegate”) some of its responsibilities to an instance of another class.

In delegation, an object handles a request by delegating to a second object (the delegate). The delegate is a helper object, but with the original context. With language-level support for delegation, this is done implicitly by having self in the delegate refer to the original (sending) object, not the delegate (receiving object). In the delegate pattern, this is instead accomplished by explicitly passing the original object to the delegate, as an argument to a method. Note that "delegation" is often used loosely to refer to the distinct concept of forwarding, where the sending object simply uses the corresponding member on the receiving object, evaluated in the context of the receiving object, not the original object.

Cookie shop should sell cookies, where Bakery should bake cookies.

struct Cookie {

var size = 5

var hasChocolateChips = false

}

// Setup delegate protocol

protocol BakeryDelegate {

func bakeCookies(cookie: Cookie)

}

// Implementation of the delegation

class Bakery: BakeryDelegate {

func bakeCookies(cookie: Cookie) {

print("Yay! A new cookie was baked, with size \(cookie.size).")

}

}

class CookieShop {

var delegate: BakeryDelegate

init(delegate: BakeryDelegate) {

self.delegate = delegate

}

func buy(cookies: Int) {

var cookie = Cookie()

cookie.size = cookies

cookie.hasChocolateChips = true

delegate.bakeCookies(cookie: cookie)

}

}

let bakery = Bakery()

let shop = CookieShop(delegate: bakery)

shop.buy(cookies: 6)Yay! A new cookie was baked, with size 6.

class Cookie {

public size = 5;

public hasChocolateChips = false;

}

// Setup delegate interface

interface BakeryDelegate {

bakeCookies(cookie: Cookie): void;

}

// Implementation of the delegation

class Bakery implements BakeryDelegate {

bakeCookies(cookie: Cookie): void {

console.log(`Yay! A new cookie was baked, with size ${cookie.size}.`);

}

}

class CookieShop {

constructor(private delegate: BakeryDelegate) {}

buy(cookies: number): void {

const cookie = new Cookie();

cookie.size = cookies;

cookie.hasChocolateChips = true;

this.delegate.bakeCookies(cookie);

}

}

const bakery = new Bakery();

const shop = new CookieShop(bakery);

shop.buy(6);Yay! A new cookie was baked, with size 6.

The facade pattern is used to define a simplified interface to a more complex subsystem.

Provide a unified interface to a set of interfaces in a subsystem. Facade defines a higher-level interface that makes the subsystem easier to use.

final class SystemA {

public func veryBigMethod() {

print("veryBigMethod of SystemA");

}

}

final class SystemB {

public func veryImportantMethod() {

print("veryImportantMethod of SystemB");

}

}

final class SystemC {

public func veryDifficultMethod() {

print("veryDifficultMethod of SystemC");

}

}

class Facade {

private let a = SystemA()

private let b = SystemB()

private let c = SystemC()

public func runBigAndImportantStuff() {

print("-- runBigAndImportantStuff started --")

self.a.veryBigMethod()

self.b.veryImportantMethod()

print("-- runBigAndImportantStuff is done --")

}

public func runBigAndDifficultStuff() {

print("-- runBigAndDifficultStuff started --")

self.a.veryBigMethod()

self.c.veryDifficultMethod()

print("-- runBigAndDifficultStuff is done --")

}

}

let facade = Facade()

facade.runBigAndImportantStuff()

facade.runBigAndDifficultStuff()-- runBigAndImportantStuff started --

veryBigMethod of SystemA

veryImportantMethod of SystemB

-- runBigAndImportantStuff is done --

-- runBigAndDifficultStuff started --

veryBigMethod of SystemA

veryDifficultMethod of SystemC

-- runBigAndDifficultStuff is done --

namespace FacadePattern {

export class SystemA {

public veryBigMethod(): void {

console.log("veryBigMethod of SystemA");

}

}

export class SystemB {

public veryImportantMethod(): void {

console.log("veryImportantMethod of SystemB");

}

}

export class SystemC {

public veryDifficultMethod(): void {

console.log("veryDifficultMethod of SystemC");

}

}

export class Facade {

private a = new SystemA();

private b = new SystemB();

private c = new SystemC();

public runBigAndImportantStuff(): void {

console.log(`-- runBigAndImportantStuff started --`);

this.a.veryBigMethod();

this.b.veryImportantMethod();

console.log(`-- runBigAndImportantStuff is done --`);

}

public runBigAndDifficultStuff(): void {

console.log(`-- runBigAndDifficultStuff started --`);

this.a.veryBigMethod();

this.c.veryDifficultMethod();

console.log(`-- runBigAndDifficultStuff is done --`);

}

}

}

const facade = new FacadePattern.Facade();

facade.runBigAndImportantStuff();

facade.runBigAndDifficultStuff();-- runBigAndImportantStuff started --

veryBigMethod of SystemA

veryImportantMethod of SystemB

-- runBigAndImportantStuff is done --

-- runBigAndDifficultStuff started --

veryBigMethod of SystemA

veryDifficultMethod of SystemC

-- runBigAndDifficultStuff is done --

Instead of creating the dependency internally an object can receive it from the outside.

In software engineering, dependency injection is a technique whereby one object supplies the dependencies of another object. A "dependency" is an object that can be used, for example as a service. Instead of a client specifying which service it will use, something tells the client what service to use. The "injection" refers to the passing of a dependency (a service) into the object (a client) that would use it. The service is made part of the client's state. Passing the service to the client, rather than allowing a client to build or find the service, is the fundamental requirement of the pattern. The intent behind dependency injection is to achieve Separation of Concerns of construction and use of objects. This can increase readability and code reuse.

Consider the case of of creation of a car with different engines.

Example:

protocol Propulsion {

func move()

}

class Vehicle {

private let engine: Propulsion

init(engine: Propulsion) {

self.engine = engine

}

func forward() {

engine.move()

}

}

class RaceCarEngine: Propulsion {

func move() {

print("Vrrrooooommm!!")

}

}

class RocketEngine: Propulsion {

func move() {

print("3-2-1... LIFT OFF!!!")

}

}

let raceCarEngine = RaceCarEngine()

let car = Vehicle(engine: raceCarEngine)

car.forward()

let rocketEngine = RocketEngine()

let car2 = Vehicle(engine: rocketEngine)

car2.forward()Vrrrooooommm!!

3-2-1... LIFT OFF!!!

Example: jsfiddle link

interface Propulsion {

move(): void;

}

class Vehicle {

constructor(private engine: Propulsion) {}

forward(): void {

this.engine.move();

}

}

class RaceCarEngine implements Propulsion {

move(): void {

console.log("Vrrrooooommm!!");

}

}

class RocketEngine implements Propulsion {

move(): void {

console.log("3-2-1... LIFT OFF!!!");

}

}

const raceCarEngine = new RaceCarEngine();

const car = new Vehicle(raceCarEngine);

car.forward();

const rocketEngine = new RocketEngine();

const car2 = new Vehicle(rocketEngine);

car2.forward();Vrrrooooommm!!

3-2-1... LIFT OFF!!!

The factory pattern is used to replace class constructors, abstracting the process of object generation so that the type of the object instantiated can be determined at run-time.

In class-based programming, the factory method pattern is a creational pattern that uses factory methods to deal with the problem of creating objects without having to specify the exact class of the object that will be created. This is done by creating objects by calling a factory method—either specified in an interface and implemented by child classes, or implemented in a base class and optionally overridden by derived classes—rather than by calling a constructor.

Consider the case of currency creation. Where we want to create a currency object depending on the country.

Example:

enum Country {

case italy, spain, denmark, ukraine, usa

}

protocol Currency {

func getFlag() -> String

func getSymbol() -> String

}

// Defining currencies based on protocol

class Euro: Currency {

func getFlag() -> String {

return "🇪🇺"

}

func getSymbol() -> String {

return "€"

}

}

class Krona: Currency {

func getFlag() -> String {

return "🇩🇰"

}

func getSymbol() -> String {

return "DKK"

}

}

class Hryvnia: Currency {

func getFlag() -> String {

return "🇺🇦"

}

func getSymbol() -> String {

return "₴"

}

}

class Dollar: Currency {

func getFlag() -> String {

return "🇺🇸"

}

func getSymbol() -> String {

return "$"

}

}

// Defining factory itself

class CurrencyFactory {

static func make(currencyFor country: Country) -> Currency {

switch country {

case .spain, .italy:

return Euro()

case .denmark:

return Krona()

case .ukraine:

return Hryvnia()

case .usa:

return Dollar()

}

}

}

let currency1 = CurrencyFactory.make(currencyFor: .ukraine)

print("\(currency1.getFlag()) \(currency1.getSymbol())")

let currency2 = CurrencyFactory.make(currencyFor: .spain)

print("\(currency2.getFlag()) \(currency2.getSymbol())")🇺🇦 ₴

🇪🇺 €

Example: jsfiddle link

enum Country {

italy = 0,

spain,

denmark,

ukraine,

usa

}

interface Currency {

getFlag(): String;

getSymbol(): String;

}

// Defining currencies based on protocol

class Euro implements Currency {

public getFlag(): String {

return "🇪🇺";

}

public getSymbol(): String {

return "€";

}

}

class Krona implements Currency {

getFlag(): String {

return "🇩🇰";

}

public getSymbol(): String {

return "DKK";

}

}

class Hryvnia implements Currency {

getFlag(): String {

return "🇺🇦";

}

public getSymbol(): String {

return "₴";

}

}

class Dolar implements Currency {

getFlag(): String {

return "🇺🇸";

}

public getSymbol(): String {

return "$";

}

}

// Defining factory itself

class CurrencyFactory {

public static make(currencyForCountry: Country): Currency {

switch (currencyForCountry) {

case (Country.spain, Country.italy):

return new Euro();

case Country.denmark:

return new Krona();

case Country.ukraine:

return new Hryvnia();

case Country.usa:

return new Dolar();

}

}

}

let currency1 = CurrencyFactory.make(Country.ukraine);

console.log(`${currency1.getFlag()} ${currency1.getSymbol()}`);

let currency2 = CurrencyFactory.make(Country.denmark);

console.log(`${currency2.getFlag()} ${currency2.getSymbol()}`);🇺🇦 ₴

🇩🇰 DKK

Ensures a class has only one instance and provides a global point of access to it.

In software engineering, the singleton pattern is a software design pattern that restricts the instantiation of a class to one object. This is useful when exactly one object is needed to coordinate actions across the system.

All database queries should be executed through only one connection.

I/O to a memorry should be through one channel.

Say hi must be told only in one way through one instance.

Example:

// final prevents class to be subclassed.

final class Singleton {

// A variable which stores the singleton object.

// On initialization This is how we create a singleton object.

static let sharedInstance = Singleton()

// Private initialization to ensure just one instance is created.

private init() {

print("Initialized.")

}

func sayHi() {

print("Hi!")

}

}

let instance = Singleton.sharedInstance

instance.sayHi()Initialized.

Hi!

// Next line will fail

Singleton()

error: Singleton.playground:21:1: error: 'Singleton' initializer is inaccessible due to 'private' protection level

Singleton()

^

Singleton.playground:8:13: note: 'init()' declared here

private init() {

^

Example: jsfiddle link

namespace SingletonPattern {

export class Singleton {

// A variable which stores the singleton object.

// Initially, the variable acts like a placeholder

private static sharedInstance: Singleton;

public id: number;

// Private initialization to ensure just one instance is created.

private constructor() {

console.log("Initialized.");

this.id = Math.random();

}

// This is how we create a singleton object

public static getInstance(): Singleton {

// Check if an instance of the class is already created.

if (!Singleton.sharedInstance) {

// If not created create an instance of the class, and store the instance in the variable

Singleton.sharedInstance = new Singleton();

}

// return the singleton object

return Singleton.sharedInstance;

}

public sayHi(): void {

console.log("Hi!");

}

}

}

const instance1 = SingletonPattern.Singleton.getInstance();

instance1.sayHi();

console.log(instance1.id);

const instance2 = SingletonPattern.Singleton.getInstance();

console.log(instance2.id);Initialized.

Hi!

0.32110868008151106

0.32110868008151106

//However, js gives you ability to do next:

console.log("🤔")

const test1 = new SingletonPattern.Singleton();

console.log(test1.id);

test1.sayHi();

const test2 = new SingletonPattern.Singleton();

console.log(test2.id);

test1.sayHi();

🤔

Initialized.

0.9238042630755623

Hi!

Initialized.

0.8771180249127926

Hi!

Hit run from debug toolbar.

In order to run/debug typescript examples run tsc -w from root of the project. And then run node filesname.js to see output in console. Or user jsfiddle link to run in a browser.

Open playground in Xcode and run it there.

- https://github.com/kamranahmedse/design-patterns-for-humans

- https://github.com/DovAmir/awesome-design-patterns

- https://github.com/torokmark/design_patterns_in_typescript

- https://github.com/VanHakobyan/DesignPatterns

- https://github.com/ochococo/Design-Patterns-In-Swift

- https://github.com/abishekaditya/DesignPatterns

- https://github.com/nslocum/design-patterns-in-ruby

- https://github.com/rust-unofficial/patterns

- https://github.com/tcorral/Design-Patterns-in-Javascript

- https://github.com/raywenderlich/swift-algorithm-club

- https://github.com/AvraamMavridis/Algorithms-Data-Structures-in-Typescript

Made with ❤️ by Dots and Spaces.